i. FIRST CRESCENT

It was Marin who signed for the certified letter. The owner of the house had died and the family would be selling it so the estate could be divided evenly between the owner’s four children. Marin and their housemates had until the end of the month to move out.

Everyone around the kitchen table had a different reaction. “Maybe we could buy it from the family,” said Annie, who was positive but impractical.

“With what money?” Marin challenged.

Annie shrugged and tossed her gray-streaked braid over her shoulder. “I don’t know. Maybe we could get a grant? Like from the Arts Council? And turn it into, like, an arts collective or something?”

“I applied for a grant once,” Perry offered. The writer of the group, he’d completed four novels in the time they’d all known each other. None of the novels had made him any money, though he continued to doggedly pursue that career path, bolstered by a very small trust fund. “Grants take a long time. Even if we could get approved for one within a month, which we can’t, they wouldn’t just cut us a check for whatever this house is worth.”

“Worth,” Marin made air quotes with their fingers. “Probably close to a million even though it needs everything.” The roof leaked, the attic was inhabited by generations of squirrels, the paint had long ago peeled off, and the porch was being seduced by gravity. It was all of those issues that had made it a cheap rental ten years ago. It was also at the far boundary of Asheville, where the pavement of Pearson Avenue dead-ended into a tangle of kudzu, just before the steep drop down to Interstate 26.

There were two houses past the community garden plot, at the end of the otherwise grand and historic street: The crumbling Victorian inhabited by Marin, Annie, Perry, and River, and a bungalow whose roof had completely caved in five years ago and was now a sort of nursery for young Sumac trees.

River, a white water raft guide during the summer, was finishing out his season. He was feeling flush with the money that had to last him until next Memorial Day (and never did). “Maybe we can find another place,” he offered, even less in touch with reality than Annie.

Marin didn’t dignify it with a response. They knew the deal: Asheville had become too popular and too expensive for artists and bohemians, though Marin didn’t consider themself especially bohemian. They’d come to Asheville in 2000, making the break from a small South Carolina town where they were misunderstood and — worse — there was no creative culture. Within a week of arriving in Asheville, Marin had found a room in a punk house, was working volunteer shifts at the Co-op for discounted groceries, and had landed a job at a record store.

Twenty-three years later, Marin held the same job. Some of their friends had questioned them — Really? You’re still there? — but why not? It was a decent gig. Well, shitty pay and no health insurance, but they could wear what they wanted, play all their favorite music, and provide a safe and welcoming space for the kids who reminded Marin of themself two decades earlier.

There was a saying about “old Asheville” folks — the punks and hippies and artists who had arrived prior to 2000 — that the city had a way of keeping those it wanted. Many people tried to land there, but were quickly washed back out. Before 2010 it was transitory. But as tourist dollars and craft beer money poured in, polishing the rough edges off Asheville’s cute, Art Deco downtown, more wealthy people picked the mountain city for retirement or vacation homes. That meant less space for the underbelly of creatives, weirdos, and lost souls who had somehow managed to carve out niches.

Marin was one of those weirdos, and as much as they complained about how Asheville had changed, they didn’t want to leave. They were comfortable. They felt accepted in the circle they’d created. Riding their bike from the record store to the Pearson Avenue house — dubbed the Pirate Ship for its ominous appearance — Marin felt their love unfurl. The ride wound through the Montford neighborhood and its grand houses. Sometimes Marin meandered through the Riverside Cemetery, past graves of famous authors. Other times they stopped at the community garden near the Pirate Ship.

The garden was a rare undeveloped acre in the popular neighborhood, and it had been garden space as long as Marin had lived in Asheville. The lot was lush with raised beds, fruit trees, and vines trained up trellises. Even in the winter, the place seemed busy. Cold frames housed hearty greens, steam rose from the compost bins, and the remaining gourds of the prolific pumpkin patch sat in quiet rows.

Many times Marin had crept over after dark to steal produce. Fat tomatoes, tender green beans, even a watermelon once. Though the sign said “Pearson Community Garden,” there were never any neighbors hoeing rows or pulling weeds. Just one small man with a large beard who waved to Marin now and then. They’d come to think of him as the caretaker.

The day of the certified letter, Marin walked to the garden and stared at it for a long time. It was October, but summer had stretched on and on. The tall okra plants were still sending out spear-shaped fruits, the cherry tomatoes were producing, too, and the apple trees were heavy. Marin was gazing at the pumpkin patch when the caretaker popped up. “Fine day for it,” he said.

“I guess.” Marin scooped their overgrown bangs behind an ear. “My friends and I — we live next door — just got thrown out.”

“Evicted?” The caretaker’s eyes widened.

“Not really. But we have to leave. Our house is going to be sold.”

The caretaker gave a low whistle.

“I wish I could live here.” Marin pointed at the fattest pumpkin. “What’s that nursery rhyme? ‘Peter Peter Pumpkin Eater, had a wife and couldn’t keep her.’”

“Yes?” The caretaker was suddenly intent.

“I don’t know.” Marin shrugged. “I’m sure I’ll figure something out.” But they weren’t at all sure. Something about being forced out of the second-to-last house in town felt final. Marin flashed a peace sign at the caretaker and headed back to the Pirate Ship.

ii. NEW MOON

Annie, who had been in Asheville the longest, told them about how, in the ‘90s, you could rent a room in one of the Montford Victorians for two hundred dollars a month. “Of course the windows leaked, the heat was sporadic, and mildew grew on everything,” she said.

Besides being a Natural Food Co-op employee, Annie also made bead jewelry, which she sold on Etsy and at local craft shows. Annie kept a jewelry-making studio in the spare room of her boyfriend Dan’s house. Dan, a carpenter, lived in a neat bungalow in West Asheville that he had renovated himself. Marin called Dan the “gentle giant” — he was large, with a bushy beard and boisterous laugh. But he was also kind and thoughtful, often bringing a homemade pie or a jar of honey from the bees he kept when he visited Annie at the Pirate Ship.

No one would call Annie the captain of the ship, but she was nonetheless central to the group of housemates. Everyone had met through Annie, perhaps more specifically, the Co-op. When River started working as a whitewater raft guide, he learned to make weekly trips to the Co-op to stock up on natural peanut butter, trail mix, and ingredients for his staple summer meal: Campfire Quesadillas. Annie, who had never met a stranger, was the person who asked River — called Joe, back then — if he had been given a raft guide name yet.

Perry lived next door to the Co-op. He was one of the residents of The Gray Rock Inn, which was built as a boarding house more than a century ago. Even in 2000, when Perry was newly graduated from college and determined to write a novel, The Gray Rock Inn was one of just a few places in Asheville that rented rooms to long-term occupants. Boarding house life suited Perry, who needed little more than a bed and a desk. The shared kitchen gave him all the social life he wanted, and the Co-op next door provided him with groceries. His trust fund, though miniscule, covered his rent and enough rice, beans, and ramen to sustain him.

Even though Perry didn’t seek out conversation during his shopping trips, somehow Annie drew him out. He found himself talking to her about his novel and even bringing her chapters to read. “He’s really talented,” Annie told Marin during one of Marin’s volunteer shifts. “Maybe the next Thomas Wolfe.”

“Is Thomas Wolfe the only local author Asheville remembers?” Marin sounded more grouchy than they felt. “What about Gail Godwin or Olive Tiford Dargan or Wilma Dykeman?”

“Well, sure,” Annie said amicably. “I was just thinking about male writers because Perry’s a guy.” She realized Marin was poised to launch into gender identity and making assumptions. Annie wanted to learn from Marin, but often slipped back into conventional thought patterns. “Let’s talk about music,” she pivoted. “What are you listening to?”

After the punk house was condemned (and later bulldozed to make room for luxury condos), Marin asked Annie if she wanted to look for a place together. Back then, Annie was subletting a school bus that was parked in the backyard of one of the Montford Victorians. But rumors were circulating that the house would soon be turned into a luxury bed and breakfast, so the school bus would have to go. By 2005, there weren’t any two-hundred dollar rooms in Asheville, but it was still possible to get a four-bedroom house on Pearson Avenue and split the cost with friends. Or even strangers found on Craig’s List.

Annie suggested Perry and River, and the four lived together in one house close to the community center, then another that backed up to the cemetery. Their third shared rental house was just uphill from the community garden, which is how Marin came to discover the lush plot of land. Often, over the years they looked at the caretaker’s little cabin — probably a garden shed, they said to themself — and thought, “That’s where I want to live.”

There were three weeks left of October. Marin had made posts in all the usual places: On Instagram, in Facebook groups, even a flyer they taped to the front desk at the record store. “Looking for Affordable Housing In or Near Downtown Asheville. Preferably Room for Four Responsible Longtime Asheville Residents. We are: An Artist, a Music Nerd, a Raft Guide, and a Novelist.” Marin even added her cellphone number to the flyer because it wasn’t the right time to worry about privacy. Almost immediately they gauged an uptick in robocalls, but no leads on a new house.

Some guy who Marin guessed to be about their age, but dressed in Dad-appropriate khaki pants and a collared shirt, pointed to Marin’s sign. “It sounds like the Asheville ‘Breakfast Club,’” he said, obviously pleased with his ‘80s movie reference.

Marin looked back, stone-faced and suddenly exhausted. That’s what they were: A punchline for jokes from wealthy tourists who were slumming it in the used vinyl store. “You’re part of the problem,” Marin said.

The guy’s face paled. He set down his Pat Metheny album and slunk off. Marin felt like a heel.

That night, the four housemates gathered around the kitchen table. It was supposed to be a house meeting. River — who had ultimately given himself a raft guide name — cooked his indoor version of Campfire Quesadillas. Annie cracked open a fresh jar of salsa and Perry nibbled at a tortilla chip. “Anyone have any thoughts on our situation?” Marin asked.

It was quiet.

“Okay, I’ll go,” Marin said. “What if we squat in the house next door?”

“The one with no roof?” Perry asked. He had simple tastes, but he did require a roof.

“Hear me out,” Marin said. “We could get a big tarp. And then we could live there while we work on it. Carpentry’s not that hard—”

“It’s kind of hard,” River interjected.

“But not impossible.” Marin wondered when they had taken over Annie’s role as the positive but impractical one.”

“Listen, I don’t know how to say this,” River said. “But I’m going to move to Madison County.”

“What?” Annie’s eyes widened behind her John Lennon-style glasses.

“One of the other raft guides said I could stay in his cabin for the winter—I guess he goes home to Florida off-season.”

“Figures.” Marin heard bitterness in their voice. But someone—many people—had multiple places to call home while they only had one, and not for much longer.

iii. WAXING GIBBOUS

The plans, or lack thereof, unraveled like a moth-eaten sweater. Marin had a lot of experience with moth-eaten sweaters. They didn’t, however, have much experience with carpentry. Creeping around the abandoned house next door, Marin sized up the rotten door frame, the broken windows, and the thick moss growing on the north side. But the foundation was solid, or so it seemed.

Marin wriggled through a window in the back of the house, where the roof wasn’t fully collapsed. Was it possible there was a room or two in good enough shape to squat? And wouldn’t it be a triumph to somehow put the sad old bungalow back together?

But inside, Marin didn’t feel hope or possibility. They felt afraid of falling through the rotten floor boards and being buried alive in the damp basement. Marin climbed back out, relieved by the warmth of golden October daylight on their face. They walked up to the community garden, hoping for late figs or early winter kale. The acreage was humming with bees. Leaves had been raked into a pile in one corner of the lot and, in the other, a compost heap boasted rich, dark earth.

Marin took a seat among the pumpkins and had nearly dozed off when the caretaker tapped them on the shoulder. “How do?” he asked. “Find a new living situation?”

“No.” Marin resented being brought back to that harsh reality, but reminded themself to be kind. “Something will work out. Always does, right?”

The caretaker shrugged. “There’s always room for you here.” He didn’t expand on what “here” meant. In Asheville? On the planet?

“Thanks,” Marin stood up and self consciously brushed the back of their pants. “That’s good of you to say.”

That night, at the kitchen table, Perry announced he was able to get a room again at The Gray Rock Inn—as chance would have it, one of the long-term rentals had just opened. There was, apparently, always room for him there, Marin thought. Room at the inn. They bit their tongue.

“It’s good,” Perry said. “I need more alone time for my new novel. And we’ll still all see each other. Nothing has to change.”

But everything had to change. Fall was shifting toward winter, the garden was moving into its fallow season, and the four friends in Pirate Ship—a unit for so many years—were suddenly scattered in different directions.

iv. FULL MOON

Marin woke to the last week of October with a head full of ideas.

- Perhaps they and Annie could petition the owners of the house to hold off on selling until spring. No one bought houses in the winter, especially not crumbling wrecks of houses that needed everything.

- Maybe moving away from downtown Asheville wouldn’t be so bad. Annie might be open to sharing a yurt in the countryside.

- Or maybe River would take them in at his cabin sublet—though Marin’s only mode of transportation was their bike, and it would be a very long commute from Madison County.

- Or perhaps there was room for a makeshift apartment in the storage room or basement of the record store. But that was kind of last ditch effort territory.

Feeling more upbeat, Marin filled their thermos with coffee and biked to the record store. It was late morning and downtown was buzzing with the leaf peepers—the tourists who came for fall foliage. At the record store, Marin was surprised to find the door unlocked and the shop’s owner waiting inside. This was a rare occurrence.

“We have to talk,” the owner said.

“Okay.” Marin dropped their backpack behind the counter and opened their thermos.

“I’ve decided to sell.”

“What? You can’t!”

The owner rubbed their eyes. “I never thought I’d be able to. But then vinyl made a huge comeback and there are newer stores willing to pay top dollar for my stock.”

“Top dollar?”

“That’s right. And I’ve had an offer on the building, too.”

“You own the building?” Marin tried to wrap their head around how a person could not only own a used record business but also an entire downtown building.

“Had too,” said the owner. “Otherwise I never could have afforded rent, as expensive as things have become.”

“Yeah,” Marin agreed weakly. “So, when are you closing?”

“Pretty much now,” the owner said. “There’s a crew coming to clean the place out in an hour.”

“An hour?” Marin echoed.

The owner held out an envelope. “I’ve paid you through the end of the month.”

But there was only a week left in the month, and now Marin was without a job, too. They unlocked their bike from in front of the store and peddled slowly back to the Pirate Ship.

Annie was in the kitchen, packing dishes into cardboard boxes. She looked up when she heard the front door and met Marin’s eye. “I have to tell you something,” she said.

“Oh no. Not you, too.”

But Annie had decided to move in with Dan. He’d asked her many times and she always insisted she liked things the way they were.

“So why now?” Marin asked, trying not to whine.

Annie twirled her braid around a finger. “It’s the end of a season,” she finally said. “Can’t you feel it?”

Marin had to admit they could. They turned and walked back out of the Pirate Ship, turned right, and made their way to the Community Garden. Everything else was dying back, but the pumpkin patch was full and bright. Marin stood among the plump gourds. “Peter Peter Pumpkin Eater,” they began.

“Yes?” It was the caretaker.

“Oh, nothing.” Marin quickly wiped a tear away. “I was just daydreaming.”

“But you were saying something.”

“Only a silly nursery rhyme. I was thinking about moving into a pumpkin and it came to me.”

“Then say it.” The caretaker’s eyes twinkled.

“Peter Peter Pumpkin Eater,” Marin began again. “Had a wife and couldn’t keep her. Put her in a pumpkin shell … oh, forget it. This is stupid.”

“Is it?” The caretaker watched Marin closely.

Marin sighed. “Fine. Whatever. …And there he kept her very well.”

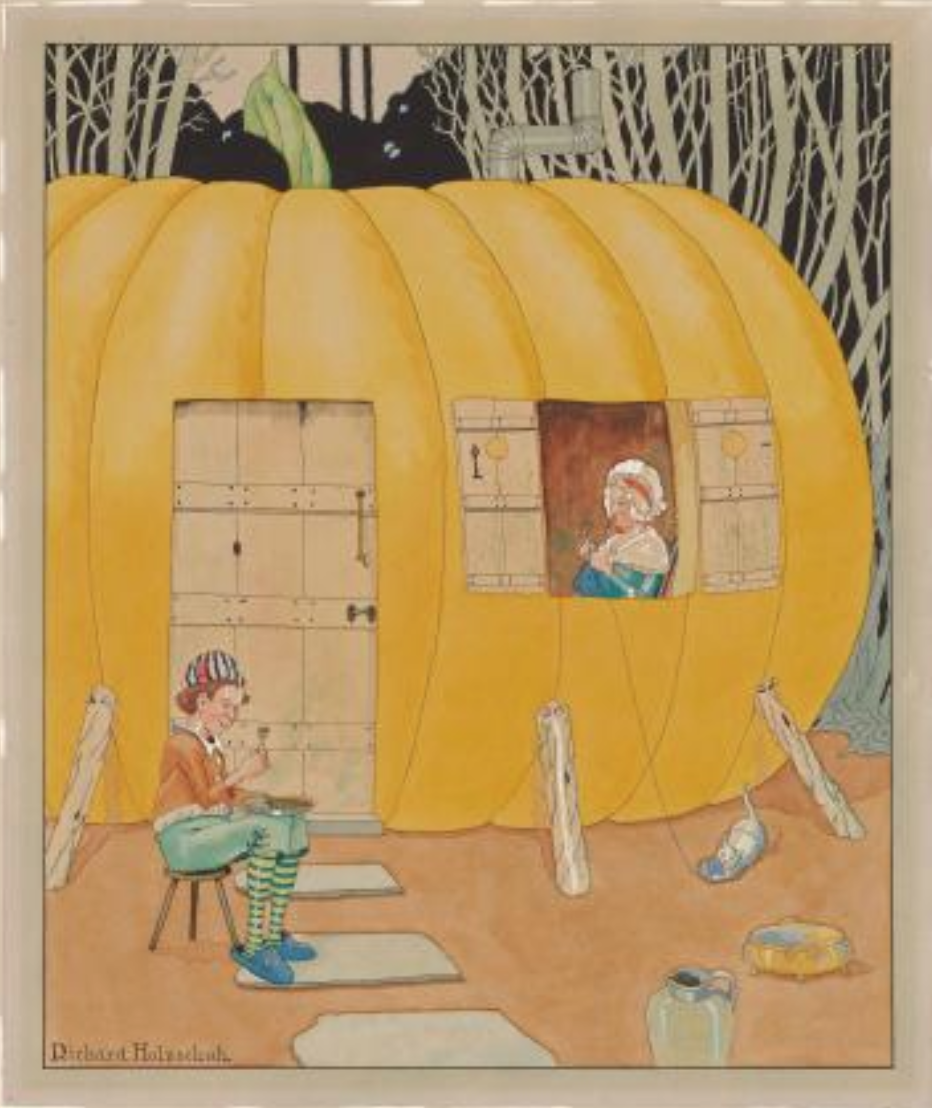

The earth seemed to spin more quickly for a moment, turning the day into a blur of red and gold and orange. There was the smell of damp earth and a bright blue flash of sky. And then Marin opened their eyes and found themself in a comfortable room. An efficiency apartment, it looked like, with hand-carved wooden furniture and a small kitchen.

The front door was cracked. Marin walked over and pushed it open. They were met with the strangest sight—a village of houses made from pumpkins. There were bikes parked in front of some. Others had flower boxes with late-season marigolds. There were clotheslines hung with fresh laundry and, on the breeze, the smell of food cooking. Birdsong was close, as was the chirp of crickets. A group of children, muddy and sunkissed, ran between the rows of pumpkins. A woman who was painting at an easel looked up, spotted Marin, and waved.

She looked familiar. An artist who had lived in Asheville wayback…

“No,” Marin said. But they knew the answer was yes. This was the Asheville at the end of Asheville—the place where old Asheville folks came when they ran out of options and ran into enchantment.

Marin was sad they hadn’t said goodbye to Annie or thought to bring their records. Hadn’t they known all along that this was where they were going? But then again, it was a whole new world to explore, and, Marin had to admit, they were ready for some new music anyway.