By Victoria Greene Maddux

Miss Asheville 1962

The summer of 1962 was a magical interlude between my first and second years in college, a season full of amazing surprises. In 1962 I was known as Vicki Greene. I was nineteen years old and home from my New England college for summer break.

Home was Asheville, North Carolina, where I deeply enjoyed growing up. It was the scene of my many youthful escapades. Far away at school for the first time, I missed Asheville, and I missed my parents who always supported my adventurous spirit.

In 1962 Asheville was a small city in a lightly populated county. The oldest mountains in the world surrounded it, mountains full of gems and crystals and flowing water. I grew up loving the southern Appalachians: their long, sensual seasons, the cool, sweet night air in summer, the endless parade of flowers, the many kinds of trees and streams.

Imagine Asheville with no interstate highways, malls, Walmarts or MacDonalds; no computers or smart phones, and only one small hospital. My family didn’t own a television until I was twelve years old. It was a black and white TV that went off the air during late night hours. Radios and dial telephones were new technology. I never saw a two-car garage when I was growing up.

I never noticed the building at 100 Biltmore. I have no memory of it at all, even though I grew up in Asheville. My friend John Senechal manages it now, or I might not know about it still. He asked me to write about my summer as Miss Asheville, but I can’t think of a single tie to the Gray Rock Inn.

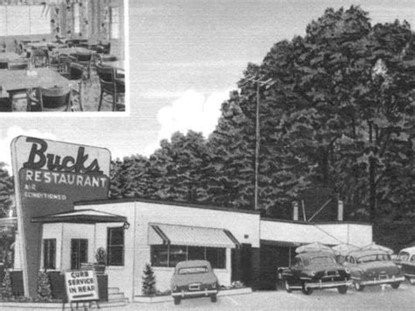

There were only a handful of restaurants in the Asheville area in 1962. The S&W was the biggest, an inexpensive cafeteria with lots of seating and rooms upstairs where diners could eat and attend meetings at the same time. My high school Latin club and toastmasters club had supper meetings there. The first drive-in restaurant opened on 3-lane tunnel road when I was in high school. We teens loved to eat at “Bucks”, (now the site of Red Lobster) after a movie at the Starlight where you watched a film while sitting in your car, and servers brought you drinks and popcorn.

The Beaucatcher Tunnel was just up the road from the Starlight, right where it is now. Just before you drove into it, there was a big sign that had amused me from the time I learned how to read. It said, “you are now entering Asheville, Land of the Sky.” Seconds later you drove into a tunnel, so dark car lights were required. (“Land of the Sky” was Asheville’s nickname). The sign only made sense when you exited the tunnel and saw Mt. Pisgah on the horizon. Now some very tall buildings obscure that view. I miss it.

George Vanderbilt, creator of the Biltmore Estate, loved Mt Pisgah so much he bought a big piece of it in 1896 from Thomas L. Clingman. It’s the view you see behind the Biltmore house.

The modern history of Pisgah National Forest begins with George W. Vanderbilt. In the late 19th century, he fell in love with the southern Appalachian mountains and forests and purchased (1896) more than 80,000 acres to surround his grand and glorious Biltmore House mansion in Asheville, NC.

In May, 1913 Vanderbilt estate officials had met with the National Forest Reservation Commission at Buck Spring Lodge offering to sell 86,000 acres of Pisgah Forest to the federal government. By March, 1914 Vanderbilt was gone, dying from complications following an appendectomy. Vanderbilt’s widow Cornelia continued to negotiate the sale of the Pisgah property, and final agreements were reached in 1916, forming the heart of Pisgah National Forest.

-Marci Spencer

In 1962 women were just starting to wear pants in Asheville. Two years before that I had to argue my parents into letting me wear blue jeans. The first jeans were all blue. Almost everyone smoked cigarettes, including doctors. Ash trays were everywhere.

When I was growing up, passenger and freight trains were a major part of Asheville’s transportation system. Imagine boarding a train any day of the week from the little station in Biltmore Village (it really was a quiet little village in 1962). In the morning, while approaching New York City, you’d be eating breakfast in the dining car.

In 1962 there were still small farms all around Asheville. Biltmore Dairy Farms supplied the city with all kinds of dairy products. “Creamline” milk came from the famous Jersey herd that grazed the Biltmore Estate’s rolling green pastures.

Asheville was still segregated in 1962: separate schools, churches, restaurants, water fountains, bus seating. In 1960 I was proud to be one of a group of black and white student leaders who, together, made those obnoxious signs that ordered African-American citizens to sit in the back of Asheville city buses disappear. But that’s another story.

Some parts of Asheville’s culture never changed. The arts flourished: visual, performing, and written. I thought of Asheville as an art colony. As a teenager, when not acting, I was singing and writing. Thomas Wolfe was one of my idols. I copied his style and memorized whole paragraphs of his work. His novels made me love words. I was proud to be a native of his hometown.

The Asheville Community Theatre (ACT) sponsored a popular children’s theatre when I was a young teen. Adaptations of fairy-tales were performed by kids, for kids. I was always in those shows. I loved everything about theatre: the scripts, the rehearsals, even memorizing lines. I loved the teamwork involved in creating a show and the fun of entertaining people. I loved becoming someone else, creating a character. Plays were a very playful activity. In high school I played Anne in ACT’s first production of “The Diary of Anne Frank.”

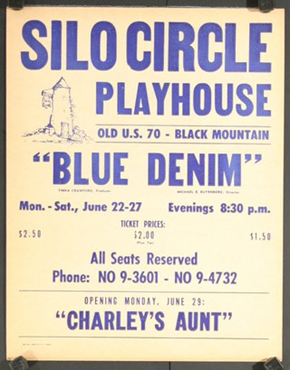

In the summer months of 1962 I was hired by a new summer stock theatre company near Asheville. Silo Circle was a “theatre-in-the-round,” a repertory company. The same actors performed a different play every week for eight weeks. Shows were performed in the loft of a huge renovated red barn surrounded by fields of corn, flowers, and contentedly grazing cows.

I wasn’t hired as an actress. Everyone in the company was from New York City. I was hired because I was local. I was in charge of borrowing all the props needed for each production, including furniture. I would help the stage manager place them for each scene and give “personal props” like handkerchiefs or wigs to the actors who needed them. Having grown up in Asheville, I could easily find anything. I enjoyed the responsibility my job required and was thrilled to be part of a professional theatre company.

I had barely settled into my work, however, when an emergency occurred. The actress who was to play all the young female roles (a different one every week) became seriously ill and had to return to New York for the remainder of the season. The company needed a new ingenue immediately, and I convinced the director that I could solve the problem.

I had attended all the rehearsals for the current production, and I knew most of the sick woman’s lines. Her costumes even fitted me. Most important, I had plenty of theatre experience. So, I took her place, proved to be a hit with audiences and reviewers, and was hired for the rest of the season. I had to join “Equity”, the New York actor’s union. My wages tripled. It was a smooth transition. I loved playing a new role every week; I was in my element.

The Silo Circle business office was always looking for publicity opportunities in the Asheville area. That summer the Miss Asheville contest was a popular news item because “Miss Asheville 1961” had become “Miss America 1962”. This gave the Silo Circle publicity director the idea that I should be a contestant for the Miss Asheville title. I resisted. Me, a beauty queen? The competition didn’t interest me. Nor did intolerance: Miss Asheville was always a white girl.

When I protested that I didn’t own an evening gown, the company costumer volunteered to make me one. When I argued that I couldn’t attend Miss Asheville rehearsals because I was performing every night, the response was “no problem”. Instead, they invited the other contestants and the judges (all men!) to see me in a show.

“We’re doing ‘Dial “M” for Murder’ the week of the contest,” the director told me. “They’ll get to see you do a death scene.” The theatre worked out a deal with Miss Asheville officials that the only time I would participate in the contest was the night it took place. The other actors at Silo Circle, by now friends, finally talked me into it.

“Just think of Miss Asheville as another role in your repertoire,” they suggested, “another character to play. It’s a no-brainer. You’ll only have to strut around half-naked once. All the world’s a stage. Become Miss Asheville.”

So, I decided to do it, although the talent competition was the only part of the Miss Asheville show I took seriously. I loved to perform, never missed an opportunity, especially if the performance expressed and communicated something I deeply believed. Anne Frank wrote, “I still believe that people are really good at heart.” Those words connected me with her spirit, and I did my best playing her, to pass on the message of hope and love.

For my Miss Asheville talent performance I prepared a dramatic monologue, a collage of passages from Thomas Wolfe’s beautiful prose about Asheville and its mountains. I rehearsed it alone and performed it once, on the Big Night – passionately. We both won the Most Talented Award – his words, my presentation.

Suddenly, I was Miss Asheville for a year. Most of that time I was an absentee “City Queen,” attending college in Vermont. My parents lack of enthusiasm about their daughter winning a beauty pageant changed when they discovered how much money I had won, two substantial college scholarships. My father actually grinned when I told him about the contract I’d had to sign to be a Miss Asheville contestant. It said the winner had to do it again, competing in the Miss North Carolina show.

Because Miss Asheville 1961 had become Miss NC, and then Miss America 1962, I had no chance of becoming Miss NC, much to my great relief, since beauty pageants made no sense to me. I did win the 1962 Miss NC Most Talented Award, the second big college scholarship.

What a summer! I became both a professional actress and Miss Asheville, each time generating unexpected prosperity. For over sixty years, memories of that long ago summer have reminded me of how creative life can be, how full of amazing, amusing surprises, with memories that make me smile, sustaining my spirit of adventure even still.