When I opened the front door, the stench knocked me back outside. It was like the time a raccoon died in the crawl space under my house. I called inside for my father, but the house was too quiet.

I had planned this trip from Vermont to Asheville to visit my dad. It took two days to drive it in my old Dodge van. I was carrying pictures from Italy, where my wife and I had just returned from a two-week vacation. My dad was Italian American; both of his parents were immigrants to New York in the 1920’s. I had a thousand questions about our Italian ancestors that I’d never thought to ask before. I had called ahead but there was no answer.

When I pulled into the driveway, the house looked the same as always. It was late afternoon, and the sun was reddening toward the western horizon. I turned the engine off and hesitated, sitting in the car. For a moment I relived old memories: baseball games with my Dad, my Mom’s pasta that was not quite Italian, some misadventures trout fishing with Dad.

I checked the mailbox on the way to the front door. My cards from Italy were there, along with about a week’s worth of mail. I turned my key in the front door and went in.

Suddenly I was a child holding my breath for as long as I could. At the same time, I was an adult ready for the worst. The smell was from the kitchen, and it spoke for who was no longer there.

The late afternoon sun shot beams across the living room where the rayon drapes hung open. I held my sleeve over my nose as I walked across the living room. Dust swirled up from my feet, unnoticed until it met the sunbeam coloring toward evening.

“Aww, Dad!” I found my father on the kitchen floor. It looked like he died of a stroke or a heart attack. He was in a robe that had fallen open. I had not seen my father naked before. I pulled the robe over his privates. There was significant scarring on his left leg and groin. He’d always had a severe limp, and was missing his left hand from that war injury in 1944.

But something else was missing. I lifted the robe again and checked. I sat back stunned and thought, “That’s why I had no brothers or sisters.” After another long moment, I thought, “It must have happened after I was born.” But the scarring seemed to be part of the original wound. Then another thought, “It might have been a later infection.” I was born in 1946, two years after he returned to the states with a purple heart medal.

Dad was a counselor. He wouldn’t talk about his clients or what he did for them. He didn’t talk much about himself either; he could keep secrets. He’d always turn a conversation around to whoever he was talking with. It wasn’t just me. There was an art form to what he did. He didn’t talk about the war, and he especially didn’t talk about his injuries unless it was a direct question. He liked solving other peoples’ problems. He dealt with his own problems privately.

I opened all the windows in the house and then carried the phone as far as the cord would reach toward fresh air. The police came, and a mortician followed. My wife Linda offered to fly from Vermont, and my daughter Alicia said she’d drive from Chapel Hill. I rented furnished rooms at 100 Biltmore Ave. for a week while the house was cleaned. The police and social services were helpful. They gave me a list: call a lawyer and a priest, pay the bills, notify friends and relatives, look for important papers like the deed, the will, and bank accounts.

The house was dirty besides smelling bad. The windows were yellowed, the kitchen was a mess. Everything needed to be cleaned and painted. I contacted Habitat for Humanity to pick up whatever they could use. Then I planned to run some stuff to the dump in my van.

The house was quiet, but not empty. In my sadness, I remembered things, the little insignificant moments that I took for granted as a child, the neighborhood baseball games, exploring the creeks, and flattening pennies on the railroad tracks. I used to enjoy helping with a church fund-raiser that my father organized every year for an orphanage in Italy.

There was a bottle of brandy on the counter next to a bottle of aspirin. I knew my father didn’t drink but kept a bottle around for “medicinal purposes.” I knew about the bottle, but it was always the same bottle, it never changed. It just emptied a sip at a time over years.

Linda and Alicia both came to help. Sorting through his stuff was tough, making piles of things to keep or throw out. Alicia found an old cat puppet named Lyon I played with as a boy. He was still in good shape; his fake fur was apparently immune to moths and decay. He had gray stripes across his back and head. One ear was ragged from too much love. His whiskers were bent from lying on his side.

Alicia slipped her hand inside and held it up. “Why hello, Bobby! It’s been a long time, I think. Judging by your advanced age, that is. How long have I been in this box?”

“It’s good to see you, Lyon. I’ve missed you.”

Alicia said, “Nonsense, you forgot about me. Don’t you have children you can hook me up with?”

“Lyon, meet my daughter Alicia. Alicia, meet Lyon the Lion. I’m sorry I didn’t introduce you sooner. Maybe there’ll be grandchildren you can play with some day. I’m still your friend, though.”

“I say, your hair is pretty thin on top. And are you getting enough sleep?”

We all laughed and then set Lyon up on the kitchen table where he could watch us as we worked to organize everything. The pictures and letters could be taken home and dealt with later. Alicia found the box of letters I’d set aside, and she read some of them.

My father had memorabilia from the war in ’44 and afterward. He had lost his left hand in the fighting, but he went back as a claims adjuster for war damages and reparations at the end of the war. If our army had needed something when they were pushing through an area, they took it. Nobody had much in those times. If the people had a claim after the war was over, we paid them. Many were worse than broke and glad to get any help after the war. Dad talked about honor a lot. Some people were too proud to ask for help, but you could tell who was desperate, he said, by their eyes.

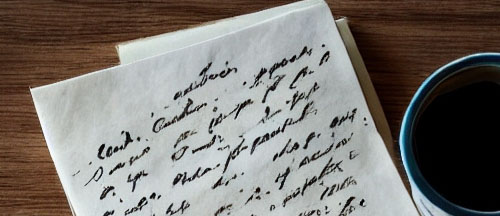

In the box of old yellowed hand-written letters, Alicia found one with a note attached. It said, “Read this, Bob.” It was originally addressed to my Mother. Alicia opened it and read it. “Dad,” she shouted, “Come and look at this!” She pulled me into the kitchen and made me sit down with the letter in front of me. “Mom,” she called. “You should read this too.”

The date on the envelope was October, 1946, from Bergamo, the same town in northern Italy where our church sponsored the orphanage. This was where my father worked after the war. I pinned the letter to the table with my index finger and thumb of each hand.

“I was writing notes, sitting on a park bench when a young girl, maybe 10 years old, came up suddenly from behind and around the bench straight up to me, and thrust a baby into my hands. In accented English, she said, ‘Take this boy away from here.’ Then she ran away before I could speak. I couldn’t put the baby down, and I couldn’t run after her while holding it. I didn’t know what to do, so I took it to the local police. They sent me to an orphanage, but the place was dilapidated and miserably overfull with war orphans.

“I started thinking of our desire to have children and the possibility that we could raise the boy as our own. I knew you would like that, and I knew how long it takes to get a reply back from you, so I have started the process to adopt him. Send me a letter as soon as you get this. I want to make sure it’s the right thing to do. He had a note pinned to his shirt that said ‘Roberto.’ And he’s from the same area of Italy that my ancestors came from. We could tell him he’s ours. it would give him a better place to grow up than here.”

My hands started to shake as I handed the letter to Linda. I was full of feelings and memories. I felt it in my heart – that ache, the love, the caring that I knew all my life. My eyes became oceans as I finally understood.

That was me, my name is Robert.

________________________________________________________________________________________

This is a work of fiction