The day the LaSalle Phaeton arrived was one of those perfect spring days. May 9, 1927. The pink dogwoods and cherry trees had dropped their blossoms, but the azaleas were in full bloom. Everywhere in Woolsey was a riot of reds and purples and the fresh green of new foliage. I was home from school — St. Genevieve — and wandering the grounds of Witchwood, playing at something or other.

St. Genevieve was a boarding school for girls, but a day school for boys. Father thought it would build character for me to be at boarding school, but Grandmother (who was my best friend) somehow convinced Father that I’d get the best education at St. Genevieve, and so I was spared living away from home. My afternoons, weekends, and summers were filled with exploring our property, just North of Asheville, and playing whatever games of make believe came to my imagination.

“Is Johnny too isolated?” Father would say over dinner now and then. I didn’t have many friends. I preferred the company of books and Granny. She, like I, was creature of Witchwood. A true citizen of our enchanted acreage. My grandfather had purchased it in 1922, just two years before he died. I think he liked it because it was grand and sprawling and important. A strange property built by Mr. Woolsey for whom our little town was named. Witchwood took its moniker from the heavily shingled and steeply pitched roofs of the house, especially one turret that resembled like a witch’s hat.

Granny and I loved Witchwood because it suited us, with its shady groves and overgrown gardens. Granny cultivated flowers, particularly chrysanthemums, and sometimes she invited the townspeople into the gardens. But as much as the townspeople liked to Ohh and Ahh over Witchwood, it wasn’t really for them. It was a place for people who had read too many fairy tales and kept too many secrets. A place for people who were more interested in the goings on of birds and squirrels than in the hectic world of business dealings.

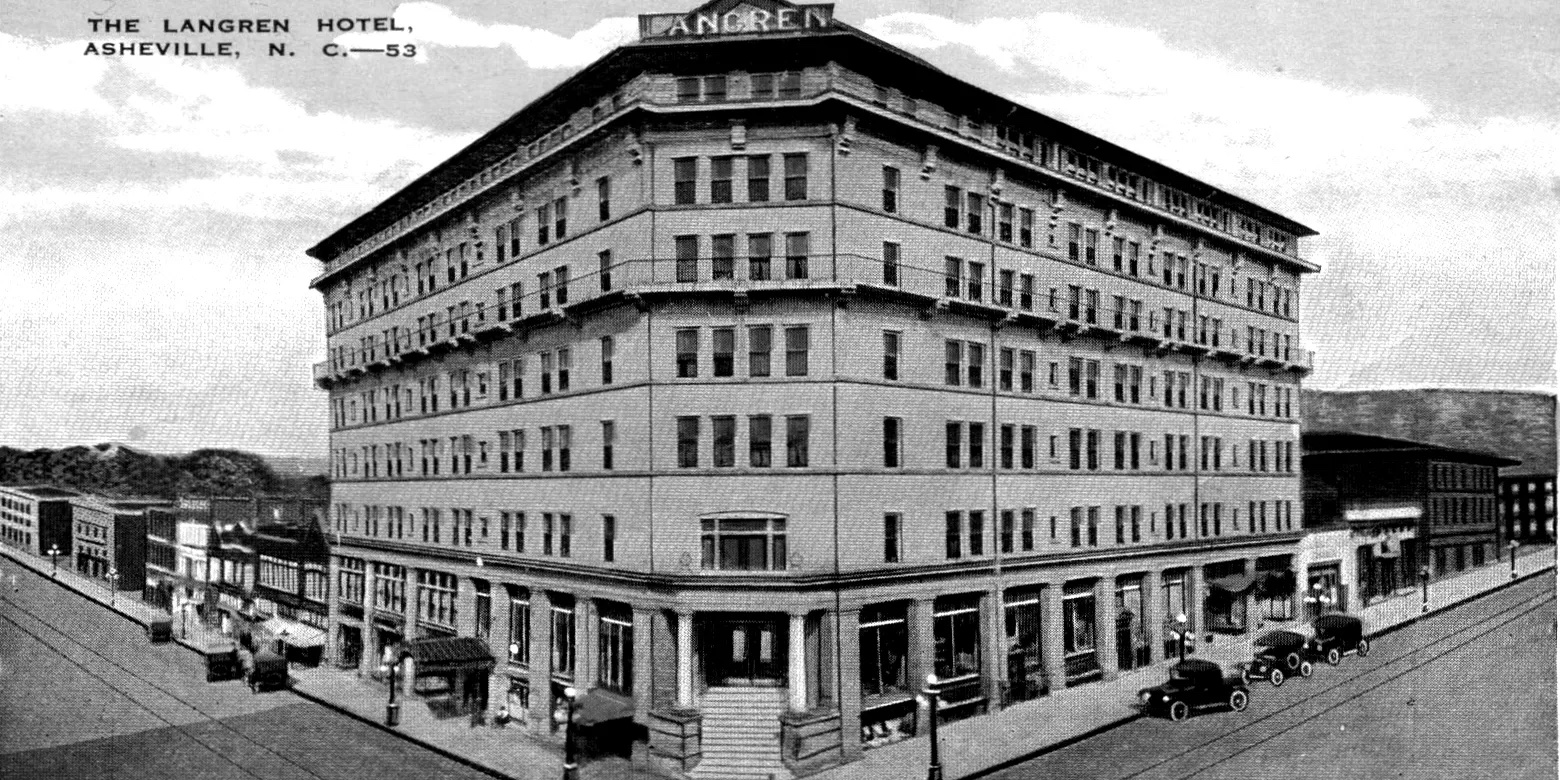

Father was very much of the world of business, though. Busying himself with men in suits and hats, shaking hands, investing in this and that. Already we had the Langren Hotel on College Street, the Glen Rock Hotel on Depot Street, and the first Cadillac-LaSalle franchise in town — all three started by Grandfather. Since Grandfather passed away three years ago, Father seemed obsessed with building the family legacy. “It will all be yours one day, son,” he said to me now and then.

But I didn’t want to run hotels and automobile franchises. I wanted to lie in a patch of buttercups and watch the clouds form shapes high above. I wanted to find ant colonies and polliwog schools. I wanted to look at bits of leaf under a microscope and marvel at the vastness of worlds that are too tiny for the human eye to see. Why should I care for building monuments and wealth when God had already engineered awe and wonder into every inch of the natural world?

Grandfather was a man of big ideas. A man with a plan. I liked him, though I found him intimidating. Forceful. It was his opinion that Asheville needed to change its reputation from a sleepy mountain town where the tubercular came to convalesce into a destination for luxurious vacations. Maybe that was also part of his plan with buying Witchwood because it was just across the way from the new Winyah Sanitarium, built by Dr. Karl Ruck. We were a stone’s throw from the man who was dead set on curing tuberculosis. (And who had also made convalescing a thing of luxury, with his spas and his sleeping porches and all.)

Like Grandfather, Father was a man of vision, too. A very particular kind of vision. One that sees Money and the Potential to Make Money. He had his imagination set on Opportunity. Hotels. The first fireproof hotel in Asheville. All the real estate he could get his hands on. He would tell you, in his grand way, perhaps casting a look at his gold pocket watch (because time is money) that You Have to Spend Money to Make Money, and that means having the nicest things, such as suits of the cream fabric specially woven at Mrs. Vanderbilt’s Homespun Shop.

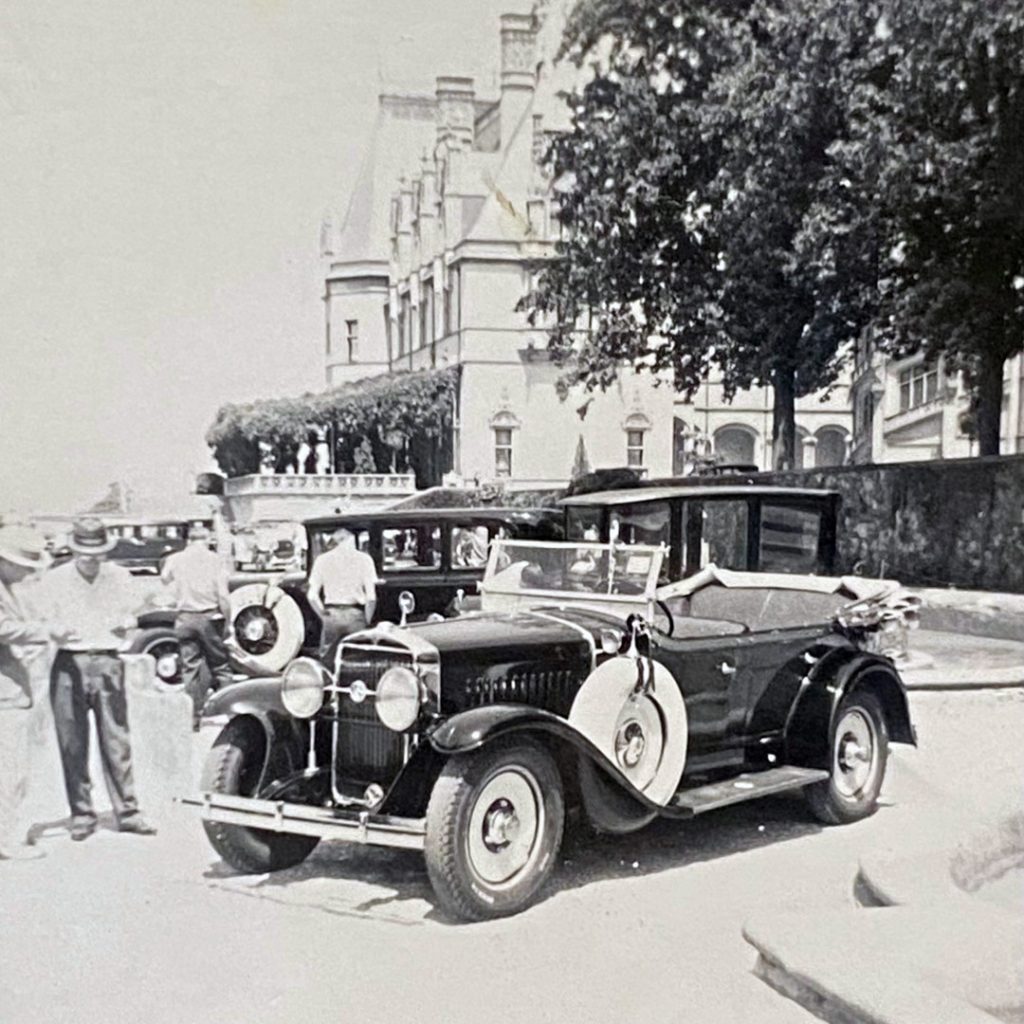

It also means having the nicest automobile, and that’s how the 1927 LaSalle Phaeton came to be ours. It was ordered directly from the factory. There were only 1,575 Phaetons produced in 1927. I know because Father said this with a kind of grave importance. “It cost more than $2,000 dollars, boy,” he said. “A Ford Model T is $369, so put that under your hat.” Our Phaeton also came with optional solid disc wheels, a $150 upgrade over wood spoke or wire wheels. Father liked fine things. The chrome bumper, the red leather seats.

We walked around the car together, me crossing my arms to mirror him, leaning back now and then to say “Hmm.” We took turns kicking the tires, admiring the spare affixed to the driver’s side, even reaching in to tap the horn, which responded with a satisfying, “ah-WOO-gah.” “What do you think of her, son?” Father asked.

“Fine,” I said. “Real nice.” I thought he’d be annoyed that I had nothing better to say. Maybe he could read my mind, which was racing with unfinished adventures on the Witchwood grounds. But that day Father was in the best of moods. The dappled sunlight of the gardens infiltrated both of us. He reached out and ruffled my hair affectionately — a move that confused me even as I found myself leaning into the warmth of his hand.

“Shall we take her for a spin?” he asked.

Though our family had automobiles — more than one, not to mention the Cadillac-LaSalle showroom — a ride alone with Father was a rare thing. I jumped at the opportunity, running to grab my cap from where I’d left it hanging off a maple branch. Father was already in the driver’s seat, the engine purring, as I climbed in beside him.

We eased our way down Woolsey Road, waving at the few neighbors who were in their yards. Mostly women tending to their flowers. As we turned west, making our way toward the French Broad River, the wind fluttered through the open sides of the Phaeton. I pulled my cap down tighter and wished for driving goggles. This, I thought, was like flying. Moving faster than a horse could trot, the smell of the water mingling with the soot of the cotton mill into an intoxicating smog. City and nature colliding and us racing through the middle of it.

We went to the Glen Rock Hotel first where father showed off the Phaeton to the desk clerk. They examined the engine together, and then wiped their hands on a clean white handkerchief. “This will be yours someday, Johnny,” the manager said to me. I wasn’t sure if he meant the car of the hotel. Both were true. I detected a glint of jealousy in his eye, but what I felt was a kind of hollow in my stomach.

The freedom I experienced in the Phaeton could only be freedom if it took me where I most wanted to be — either back at Witchwood or at some even more enchanted place that I hadn’t yet discovered. If it only carried me from one of Father’s businesses to the next, I didn’t want it. I’d be satisfied with the $369 Ford Model T. Or my bicycle, currently dumped unceremoniously alongside the porch, waiting for my return. It had always shuttled me faithfully wherever I desired to go. Reed Creek and Glenn Creek, both just down the hill from our estate. The wooded lot with the old dairy and the rumor of unmarked graves. The remnants of earthworks remaining from the Battle of Asheville more than sixty years earlier. Places a car couldn’t go.

But father was ready to drive again and so I returned to my copilot position. Wind whistling in my ears as we headed up Main Street, away from the river and the Vanderbilt estate, climbing the long hill back into downtown Asheville. We’d stop at the Langren Hotel and the Cadillac-LaSalle franchise where Father could show off his prize, shake more hands, maybe lighting a cigar as other fellows clapped him on the back.

The fruit of his labors, he’d say. The reward for all of his hard work. But I couldn’t help thinking if didn’t need the fine things — the gold watch, the cream-colored homespun suits, the LaSalle Phaeton — he’d have more time to look into microscopes and examine ant colonies and collect tadpoles in the creek.

We slowed as we entered downtown. A man on the steps of a handsome gray stone building flagged father down. “Is that the new Phaeton?” he called. Father eased to the curb and idled the motor. “Yes, sir,” he said proudly. The gentleman circled, blowing out an appreciative breath. More automobile talk ensued, so I used the time to look around. “Flora Sorell’s Boarding House,” the sign read. “Clean rooms, home-cooked meals.” Three stories with a balcony on top that surely afforded a view of the city.

Guests were sitting on the sunny porch, some reading and others smoking. A plump woman in an apron appeared and swept the steps. Maybe she was a housekeeper or maybe Mrs. Sorrells herself. I looked the look of the place, simple and cozy.

As father revved the engine and pulled back into traffic, I tugged his sleeve. “What about a boarding house?” I asked. “It’s like a hotel but less … fancy, right?”

“You saying you want me to get into the boarding house business?” Father laughed. Still the light mood of the day was with him. He was almost entertaining my idea.

“It seems easier. Not so fussy,” I said, trying to get the words right.

But the grand Langren Hotel was just ahead of us then. Its seven stories loomed large over the bustling streets. Automobiles were parked, guests checking in, bellhops loading trunks onto carts. It was rather like an ant colony — a whirl of activity and energy — and father, I could see, delighted in being at the center of all.

I longed to watch the scurry and commotion from a quiet distance while father was forever striving to orchestrate the activity.

“Boarding houses are the past,” he said, chucking me softly on the cheek. “What we’re building, son, is the future.” He killed the motor there, in the middle of check in at his busy hotel, and stood alongside the Phaeton. It was one of father’s rare moments of stillness — a held breath — pausing while everyone else noticed and admired him.

He was a lead actor about to step into the spotlight. No, not step at all. The spotlight would come to him. It always did.